I recently received the following email from a past client, and thought this would make for a great blog post topic:

After the rain tonight we noticed some water trickling out of a pipe in the wall behind the boiler and have no clue what it is for. It is located directly below the vent(?) for the boiler (which was put in after our inspection.) Matt cleaned all the vines off today, which were covering the top of the chimney, so I’m guessing that may have made a difference, but what is the purpose of this pipe? We really would like a dry basement! See picture below.

That’s a great question. That pipe that has water coming out is actually a drain, to allow water to come out of the vent. It’s really just doing what it’s supposed to do. Allow me to explain.

A large portion of the masonry chimneys in Minneapolis and Saint Paul have three layers; bricks, a clay liner, and a metal liner. The bricks are the part that make up the structure of the chimney, the clay liner typically consists of large clay tiles stacked together, and the metal liner consists of numerous sections of single-wall metal venting screwed together. The purpose of the metal liner is to protect the chimney walls from the corrosive byproducts of natural gas combustion.

The photo above shows a typical chimney setup. Can you see where water gets in? There are actually two places. Here’s another chimney with a different shape, but it’s the exact same setup. I marked up this photo to show where water will get in.

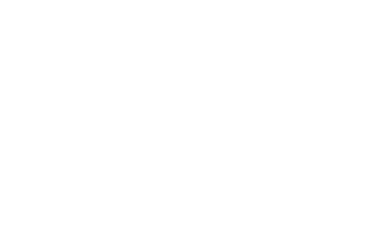

When water enters the metal vent liner, it needs to drain out. There’s where the little hole in the chimney comes in. There is also a blocked off pipe sticking out of this chimney near the drain; the purpose of that pipe is to support the weight of the metal liner. It goes right through the chimney.

So there you have it. The water the comes out of the drain shouldn’t be much, and is mostly just a nuisance. Some people hang a small pail below this drain to catch the water. While that seems a little ‘hacky’, there’s really nothing wrong with it, but my preference would be to stop water from coming in at the top of the chimney. As mentioned above, there are two holes to cover; the opening in the metal vent liner, and the space between the metal vent liner and the clay liner.

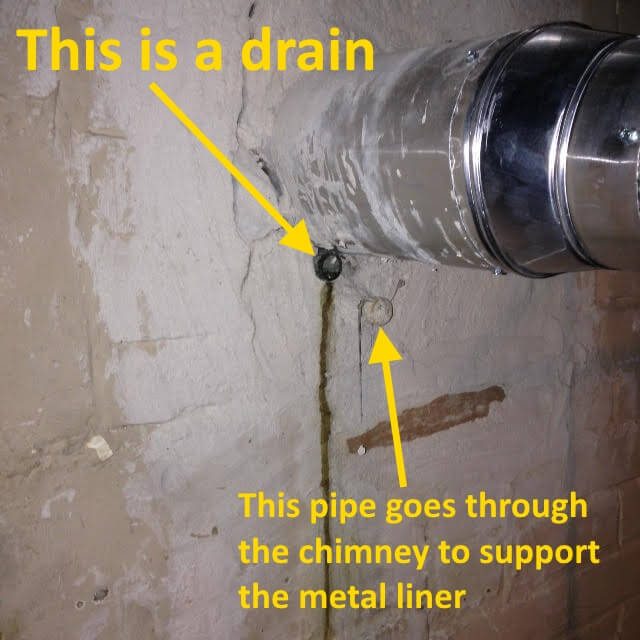

Preventing water from coming into the metal liner is simple and straightforward; install a listed vent cap at the top of the vent. The example at right is just one type; there are probably about a dozen different styles. Not only will this prevent rain from coming in, but it will also help to prevent downdrafts and prevent pests from getting into the vent. You’ll need to measure your vent diameter to pick up the right size; the most common sizes are 4″, 5″, and 6″. These vent caps sell for around $10.

Preventing water from coming into the metal liner is simple and straightforward; install a listed vent cap at the top of the vent. The example at right is just one type; there are probably about a dozen different styles. Not only will this prevent rain from coming in, but it will also help to prevent downdrafts and prevent pests from getting into the vent. You’ll need to measure your vent diameter to pick up the right size; the most common sizes are 4″, 5″, and 6″. These vent caps sell for around $10.

If the vent cap simply looks like a bent-up piece of sheet metal, it’s surely not a proper vent cap. These old / improper caps can allow for water intrusion, pest intrusion, and the support arms can collapse. I have two examples of such improper caps shown below.

Preventing water from entering the space between the metal vent liner and the clay liner is a little trickier, but still not a big deal. Simply cut up a piece of sheet metal to fit over the metal vent liner, and caulk it in place at the clay liner. The photos below show a few examples. None of these are perfect, but they’ll all get the job done.

If you don’t have any great way to cut a nice round hole in the sheet metal, slip a storm collar over the vent onto the sheet metal. Here’s a diagram of a storm collar:

And here’s what it looks like installed:

The one bit of caution I have before covering the space between the metal vent liner and the clay flue is that every once in a while, I’ll find the water heater venting into this space. If that’s happening, blocking the opening will cause the water heater to backdraft, and potentially fill the home with deadly levels of carbon monoxide. This is why it’s a good idea to hire professionals to do this kind of work.

So there you have it. If your chimney doesn’t look like these examples, don’t worry. It’s not that big of a deal.

Author: Reuben Saltzman, Structure Tech Home Inspections